The Jonestown Massacre. Any mention of Guyana, and I’m guessing it’s the Jonestown Massacre that comes to mind. Ponder the subject of Guyana and its infamous massacre any further, and this is what you’ll likely recall: how, in November 1978, at an agricultural commune in a densely jungled part of the South American country, the American expat and religious wingnut, Reverend Jim Jones, head of People’s Temple and all-around frothing-at-the-mouth, crazy-ass motherfucker, forcibly coerced most of his cult—909 members in all—into killing themselves by drinking cyanide-infused Kool-Aid and then dying, one atop the other, in the tall, green grass of an open field, in stinking mounds of death, two and three people high. Most mentions of Guyana, for most people of a certain age, at least, trigger memories of that terrible event. Images from the massacre are horrific, the kind of thing one forever wishes to unsee. For those of us alive in 1978, and who first learned of the slaughter on television, as ABC cut away from Happy Days and Laverne & Shirley to show us dead countrymen stacked like firewood across a Guyanese jungle, we decided, collectively and most emphatically, to remand Guyana to a list of shit-hole countries to which no American worth her salt would ever again pay heed.

Which was a mistake. Big time. Because Guyana, it turns out, is a veritable Brigadoon, one nestled in the lush, rain forests of South America, a verdant wonderland, in fact, Eden-like in its unsullied, natural beauty, and peopled with some of the kindest, gentlest, most giving souls I’ve yet had the good fortune to encounter. I’ve been coming here, to Guyana, and to its capitol city, Georgetown, every month for nearly year to help a certain energy company craft culinary experiences for visiting company executives. Across this last year, I’ve come to love Guyana for all the ways it’s unlike any place I’ve ever been: for its skinny-ribbed dogs roving in packs along its shitty, washed-out dirt roads; for its unrelenting, sauna-like heat, rolling in waves from out of its jungles; for the way the smell of Guyana itself somehow evokes the redolence of ancient plant-life decaying in river mud, an odor immediately palpable to any arriving visitor, so like smelling salts for the way it instantly enlivens one’s sense of where one’s just landed.

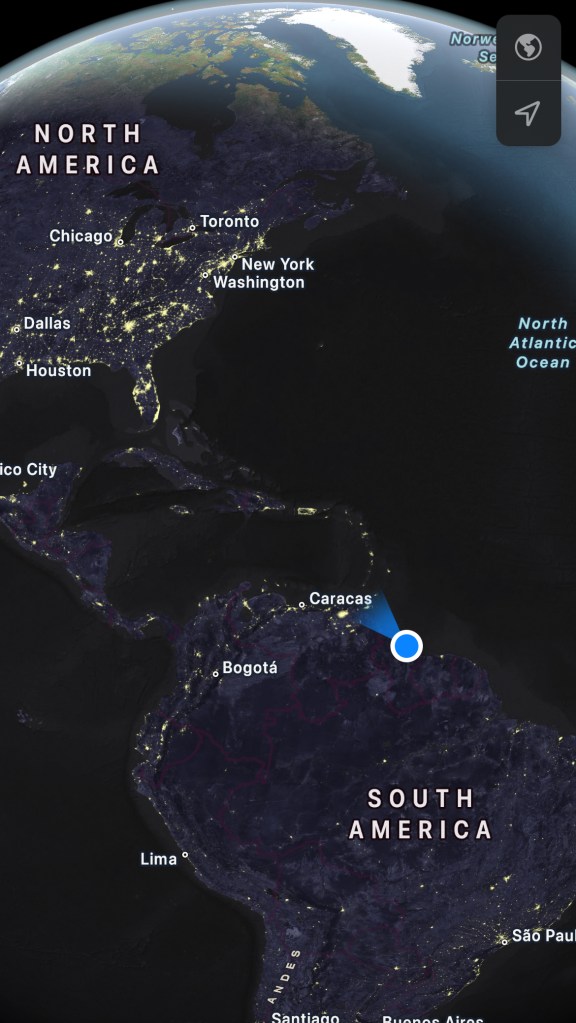

Guyana sits on South America’s north-Atlantic coast, at ocean’s edge, neatly wedged between Venezuela (to its west) and Suriname (to its contiguous east) with vibes—and weather—unmistakably Caribbean. Because of its immediate proximity to Venezuela and its relative closeness to Brazil, I expected Guyana (culturally, ethnically) to be an extension of greater Latin America. I expected it to be speaking Spanish and/or Portuguese. I expected to salsa dance and feast on decidedly Latin flavors. Everything I expected was wrong.

Because zero, exactly zero: that’s how much Spanish influence I’ve since detected in Guyanese culture. Instead of some Latin American outpost, imagine Guyana as the love child of India and Senegal, one who grew up in South America, darkly complected, and speaking the King’s English under strict, British-colonial rule. Imagine that, my friends, and you will have succeeded in conjuring the Guyana of today. Ethnically, Guyana’s population is roughly 40% Indian (eastern, not indigenous), 30% African, with 20% of Guyanese nationals being an admixture of the two.

This extraordinary polarity (and occasional clash) of its two dominant cultures—Indian and west African—appears everywhere in Guyana. It shows up in its politics—an ethnically Indian president constantly at odds with an Afro-centric opposition party—and in its popular religions, which manage to simultaneously celebrate Hinduism, Islam, and Catholicism across its respective houses of worship. But it’s in Guyanese cuisine that visitors, like me, divine a more articulate understanding of how the interplay of the country’s disparate influences manifest in the flavors of its foods: proto-Amazonian ingredients (yucca, plantains, catfish), prepared with traditional Guyanese technique (chunkay tempering, for example, whereby spices—say, cumin seed and garlic—are toasted in hot oil to coax aromas), and then seasoned with spices most often associated with India (garam Masala and curry powder). It’s a kind of culinary madness, this food of Guyana, and the results are utterly amazing. Because from this gastronomic schizophrenia comes Guyanese classics like Pepperpot (meat stewed with cassareep, cinnamon, and cloves), Metemgee (soup made from cassava, coconut milk, fish), and Guyanese curry—yellow, red or green—served with an obligatory portion of dhal puri flatbread. We’re talking deeply delicious food.

Throughout this last year, I’ve enjoyed every one of Guyana’s national dishes in the dining room of my hotel, and in my hotel only. Yep, you read that right: until very recently, I’d dined nowhere else in Guyana outside the purlieus of my hotel grounds. Not at a local Georgetown restaurant. Nor at some local coffee shop or café. I’d eaten nowhere else save for my sad, little corner table, inside the prison that had become my culinary home: the fucking Marriott International.

This was not my fault. Not really. Because upon my hiring, the energy company responsible for signing my monthly paychecks decreed that at no time during my employment was I to venture outside my hotel, or stray beyond the corporate confines in which I worked. Not on foot, nor in any cars other than those provided by the company. I was remanded to occupy only those two places: my lodgings, and my place of business. Nowhere else—not nightclubs, not shops, not eateries—could I permissibly go.

To be fair: company concern for my safety was not entirely unfounded. The United States Department of State puts Guyana at a Level 3 on its threat scale, a number which compels the agency to urge travelers, like me, to “reconsider travel” due to “violent crime, including murder and armed robbery…especially at night.” There I sat, inside my fucking hotel, desperately trying (and occasionally succeeding) to tease some sense of Guyanese authenticity from every meal I ate.

So I stayed put, inside my hotel, until I could take it no more. After months of culinary captivity and exile, I decided to bolt. To make a run for it. I decided to bust out. On a sunny day this September, I fled the Marriott on foot. I walked out the front hotel doors, nonchalant as a cool breeze, and seemingly without a care in the world. I went afoot across the streets of Georgetown, walking fore and aft, north to south, this street and that, until I chanced upon The Cottage Restaurant and Café, exactly the kind of Guyanese hot-spot for which I had long been pining.

More walk-up cabstand than traditional eatery, The Cottage offers tried-and-true, low-cost Guyanese dishes for the hungry masses, served in plastic clamshells, and dispensed with demonstrative glee through a single, sliding service window. The Cottage was teaming with eaters the afternoon of my visit, locals and taxi drivers alike, all gathered on The Cottage’s concrete patio, under a metal awning, bouncing foot-to-foot in anticipation of their orders soon being ready.

When it was my turn to order, I asked for curried chicken, and then pressed my nose to the glass window to watch my clamshell fill with rice and curry, scooped from hotel pans seated in a long steam-table along the restaurant’s bare-bones kitchen. I also looked on as last corner of that same clamshell was filled with a handful chopped greens, the token, salad portion of my meal. Even through all that glass, the smells of The Cottage were incredible: turmeric, cumin, and coriander, each spice like culinary fairy-dust, borne up on sunlight to better perfume the noonday air.

The service window soon opened, and out came my clamshell: over two pounds of rice and chicken curry, served with a Styrofoam cup of green-lentil dhal, all for $6.70 USD. I took my food with thanks, and then sat on a curb just beyond The Cottage’s parking lot. With my restaurant-issued plastic fork in hand, I bent to my meal and ate.

This was no ordinary chicken curry, dear friends. This stuff was special: local yardbird—bones and all—stewed in a stock of its own making and spiced with lemongrass, galangal, and makrut lime accompanying the ubiquitous cumin and coriander. This curry was then heaped over white rice so profoundly (and purposefully, I’m sure) overcooked as to form a kind of paste evocative in taste and texture of Senegalese Fufu.

Delicious as the curry was, the green-lentil dhal proved utterly transcendent, the star of the show: lush, silken, bright, and umami-rich, with notes of mustard seeds, garlic, and yes, turmeric, brightened by a quick frolic-in-the-pan with hot ghee. Drinking that dhal (I had no spoon) was like tasting a Guyanese cloud: light, amorphous, and ethereal. It was a miraculous cup of food, that dhal, and it remains one of my favorite bites of the entire year.

It’s become cliched in food-and-travel writing for blog posts like this to too-neatly alight on epiphany at their end, and to all-too-conveniently arrive at the inevitable conclusion that traveling to strange lands is a good thing (always), and that feasting on gastronomic exotica invariably delivers insight and reward to its eater (ibid). Hackneyed and boorish as that too-rote summation is, these things are, in fact, very much true: eating weird shit on a dirty road does, indeed, halo the traveler’s head with the fire-fury of realization, and sets to dancing the nimbus of actual enlightenment. For to discover gastronomic greatness inside a Styrofoam cup, while seated on curb of a South American street, inside a deeply impoverished, developing nation (as did I in Guyana, drinking that dhal), makes axiomatic, I believe, and for the zillionth time in food writing like mine, the irrefutable truth that all adventure—traveling to challenge, even imperil one’s own sense of comfort while seeking strange, new lands—makes a conduit of the soul, one ready to receive all things in forms both extraordinary and sublime.

Even in a place where 909 Americans were once murdered by one of their own.

And especially in a place where you get a cup of fucking good dhal.

Contact: christopher@proletariateats.com

Leave a comment